Part 3: California Dreamin'

“I’ve got five miles of range left on reserve,” I muttered nervously through the helmet comms to Florian and Caleb as we passed a sign that said the next fuel stop was 24 miles away.

“Crap, I’ve got seven,” Caleb chimed in.

I still don’t know how it happened. Maybe we got some bad fuel, or maybe the desert heat interfered with filling the tanks completely at our last stop. Either way, my fuel light had been flashing for the past 30 miles—and I hadn’t even noticed. Running out of gas in the middle of the desert was definitely not on my Route 66 bucket list. Without another word, our three Harley-Davidsons slipped into a narrow flying formation. We eased into a more fuel-efficient pace and lined up behind Florian, who somehow still had plenty of go juice.

I tucked in behind my fairing, fingers hovering over the brakes as I used Florian’s bike to shield mine from the wind and conserve energy. Caleb did the same behind me, riding two layers deep in the slipstream. We became a single moving unit; smoother, faster, and more efficient than if we’d been riding solo. In moments like that, communication and trust are everything. The spacing has to be tight enough for you to stay in the aerodynamic sweet spot. It’s a calculated dance of three machines slicing through the desert air as one.

I watched the numbers on my odometer tick down until they hit zero. If I hadn’t already been sweating buckets from the heat, that would’ve done it. We were locked in, calling out every move before making it. And then, with a collective sigh of relief, we sputtered into a gas station in Santa Rosa, NM.

Motorcycles & Gear

2024 Harley-Davidson Road Glides and Street Glide

Helmet: HJC RPHA 11 Pro, Arai Signet Q

Pants: Klim Outrider Pants, Klim K Forty 3 Riding Jeans

Jacket: Klim Induction, Klim Marrakesh, REV’IT! Overshirt Tracer Air 2

Boots: Klim Black Jak, Danner Logger, TCX Hero 2 WP

Gloves: Klim Dakar, Alpinestars

Luggage: Peak Design 45L Travel Backpack, Peak Design 30L Travel Backpack

Comm System: Cardo Packtalk Edge (seven of them)

Camera: Nikon Z6II, 24-70mm F2.8, 28-300 F3.5

Pressing Pause

This gas station not only had cold drinks and fuel, but also an attached post office. We grabbed a spot at the picnic table and took a few minutes to scribe messages on the backs of postcards we’d picked up a few days earlier. There was something timeless about pausing to put pen to paper. In the golden age of Route 66, a handwritten postcard was the heartbeat of roadside communication. I can only imagine how many of those little cards were sent from the Mother Road during its prime. The number must be staggering—millions of tiny stories sent off to faraway mailboxes.

After licking the stamps and sliding our cards into a faded blue mailbox, we saddled up again, engines rumbling to life. With our tanks topped off and a few messages bound for home, we rolled back onto the Mother Road, enriched by a quiet moment that felt like it could have happened 70 years ago.

Old Route to Santa Fe

The original Route 66 once curved north to Santa Fe, but it was realigned in 1937 to bypass the city, shaving 107 miles off the route. Determined to follow as much of the original alignment as possible, we split off and headed north on SR 85, tracing the pre-1937 path toward the capital of New Mexico.

As the landscape has transformed before from the green Midwest to the dry and arid Texas (Aug ‘25 issue), it did so again. This time, desert gave way to rising mesas, thicker brush, and clusters of trees that hinted at a wetter climate and higher elevation. We climbed steadily, gaining over 3,300 feet as we approached Santa Fe, which sits at 7,300 feet. The air cooled slightly with the climb, offering a modest break from the heat, although it was still stiflingly hot as we made our way through town. Toward the end of the ride, a passing storm rolled in, and we welcomed the cool drizzle as it filtered through our mesh jackets.

At last, we pulled into the El Rey Court, a classic adobe-style motor lodge. RoadRUNNER founders Christa and Christian Neuhauser had stayed here during their Route 66 trip years and years ago. Strings of chile peppers hung from wooden beams, swaying slightly in the breeze. The scent of grilled meat drifted through the air, and we followed our noses around back to a food truck, where the cook was smashing burger patties onto the griddle like it was a race against time.

Spirit Arrows

Continuing westward through New Mexico, we began crossing Native American reservations. It’s tricky to stay on the original route in this part of the state, because many of the side roads take you onto reservation land. Traveling through without permission is frowned upon in many places. Much of the original route is covered by I-40, so we took turns riding on the interstate and checking out the parallel road to see if it goes through. We got lucky in some spots, but also had to backtrack a few times. At least the side quests broke up the monotony of interstate travel.

Dead Man’s Curve in Mesita, NM, is one of the most infamous and dramatic bends along old Route 66. Although there are many turns that share the moniker, this curve is located near the Laguna Pueblo lands west of Albuquerque. It earned its nickname from the many accidents that occurred there, especially during the heyday of the Mother Road. It was going to make a great photo op, so we stopped to document the dramatic red cliffside and the corner that was nowhere as sharp as the twists and turns of the Appalachian Mountains back home.

Out of nowhere, in the middle of the corner during one of the photo passes, Caleb’s bike gave out. Dead Man’s Corner lived up to its name, but this time it was the machine that didn’t make it. We concluded it must have been struck by a spirit arrow, fired not in anger but to force us to stop in the middle of the desert for some unknown reason.

The sun beat down as we assessed the situation. The motorcycle sat just off the shoulder of the road. In the distance, a hauntingly melodic tune drifted through the air, echoing off the cliffs. The song, played on a Native American flute, felt like a tale carried on the wind that the ancient people of this land wanted us to hear. It was a gentle reminder to slow down and feel the heartbeat of Route 66 beneath our boots. The hardships we faced had made us part of its long asphalt-layered story in a very real way.

We were able to get the bike towed to Thunderbird Harley-Davidson in Albuquerque, and subsequently rented a replacement from their EagleRider fleet to finish the trip. The dealership even had a Road Glide in the same color. We rolled into Gallup, NM, as the sun set in front of us. What was supposed to be a short-distance day filled with photo stops had turned into a very long one, with the added headache of making sure the trip continued on. Ultimately, we succeeded, and a juicy rib-eye steak and enchiladas put us all quickly to bed.

Totally Petrified

We lucked out with a slightly overcast morning, which brought some relief from the heat. The soft light made the pastels of the Painted Desert come alive. Rather than continue along I-40, we took a slight detour into the Petrified Forest National Park, the only one that Route 66 once passed directly through.

The park is best known for its uniquely preserved logs, remnants of an ancient forest that thrived over 200 million years ago. Back then, this region was a tropical floodplain, rich with towering trees and other plants. After natural forces wiped out the forest, a perfect combination of moisture, sediment, and volcanic minerals preserved the fallen trees, turning wood to stone. Today, fragments of these colorful, fossilized giants lie scattered across the desert floor, blending seamlessly into the surreal landscape.

We took our time cruising through the park, stopping now and then to admire the massive petrified logs and the view, which looked more like a watercolor painting than real life. At one point, we spotted a line of weathered telephone poles stretching into the open desert, seemingly leading nowhere, and pulled off the road. Although the pavement has long since disappeared, the poles still mark the original alignment of Route 66 through the park. Today, shrubs have reclaimed the path, and travelers choose between I-40 or the quieter, more scenic Petrified Forest Rd—as we did.

Rolling into Holbrook, AZ, we were on the hunt for yet another photo to recreate. This time, our target was Joe & Aggie’s Cafe, a Route 66 staple. We found it easily. The exterior hasn’t changed a bit in 30 years. It’s almost as if places such as this were preserved in time, just like the prehistoric logs. That evening, standing outside our tipi-style rooms at the Wigwam Motel, we watched one of the most colorful sunsets I’ve ever seen. And as if on cue, a giant double rainbow, our second of the trip, arched across the sky above us.

A Treacherous Journey on Oatman Highway

In the early days of Route 66, the section that wound through the Black Mountains of Arizona—now known as Oatman Highway—was one of the most dangerous and harrowing parts of the entire route. Narrow and clinging precariously to the mountainside, it was carved into steep switchbacks with sheer drop-offs and no guardrails. Early travelers, especially those in overloaded Model Ts or dust-choked caravans heading west during the Dust Bowl, often faced overheating engines, failed brakes, and white-knuckle climbs up the twisting grade known as the Sitgreaves Pass. The descent was no less perilous. Locals, well aware of the road’s reputation, would offer to “drive you over the mountain” for a small fee, sometimes saving lives in the process.

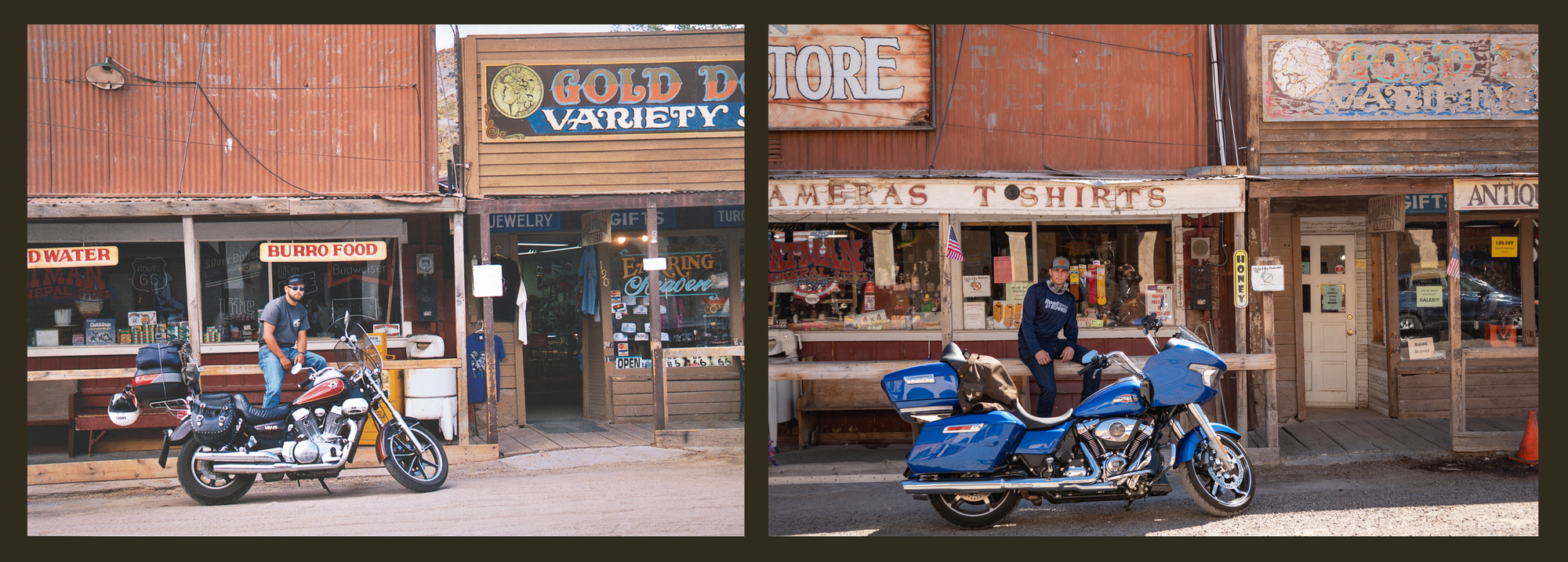

Despite its dangers, Oatman Highway was a vital link between Kingman and the Colorado River crossing into California. It was a turning point in the route, one last challenge before entering the promised land of the West. We zigzagged our way up Oatman Highway, being doubly cautious on the dust-covered asphalt. At its highest point, the highway sits around 3,550 feet in elevation. We were glad to be riding modern bikes with good braking systems. Rolling into the old mining town of Oatman, the first thing I heard was: “What are these donkeys doing on the sidewalk?” Florian had spotted the first of many wild burros that now roam freely through town. With its dusty streets, weathered wooden buildings, and open-faced storefronts, Oatman radiates a Wild West atmosphere. The wandering burros really drove it home.

You might wonder just how “wild” these donkeys really are. They've grown quite accustomed to humans, often lingering near shops hoping for a treat or a scratch behind the ear. Locals not only recognize each of the regulars, but many know them by name and personality, treating them more like town mascots than wildlife. We lingered for a while, sipping fresh-squeezed lemonade, feeding the burros, and browsing a few of the quirky antique shops. To our delight, some of them featured vintage motorcycles among their dusty treasures.

The Final Stretch

As we descended the western slope of Oatman Highway, the temperature began to climb. We’d been battling triple-digit heat for most of the trip, so seeing the thermometer hit 103 didn’t come as a shock.

But it quickly hit 109, then 113—and the number just kept rising. By the time we reached the bottom and rolled into the Mohave Valley, the bike’s reading stood 116 degrees. As we rolled into Needles, an outdoor meter on the side of a building read 121. According to the local weather report, it “felt like” 134. To me, it felt like my skin was melting.

We quickly learned it was best to keep our faceshields down. Riding with them open felt like sticking your head into a blast furnace. Our GoPros shut down, unable to handle the heat. At one point, I reached for the clutch lever and, even through my gloves, it burned my fingers. “It’s so hot, I bet you could fry an egg right here on the road,” I said to the boys as we crossed the valley floor. We joked about fried eggs until we realized we were too late. A recent egg-frying contest had cleaned the shelves of every store in town. Next time I ride a Harley-Davidson through the desert, I’m bringing my own eggs.

As we rolled into Santa Monica, the final miles of Route 66 stretching out behind us, a strange mix of emotions settled in. After 17 windburned, sun-soaked, and road-weary days in the saddle, we had finally reached the end of a journey we’d each dreamed of for years.

There was joy, of course, and a deep sense of accomplishment. We’d done it. We had followed the Mother Road from Chicago to the Pacific Ocean through forgotten towns, neon relics, and long stretches of solitude. But, beneath the excitement, there was a quiet melancholy—the kind that lingers when something beautiful is coming to an end.

We had traveled through time, uncovering stories in layers of asphalt. We put ourselves in the shoes of those early travelers who once made this trip when the road was a symbol of hope, escape, and discovery. Also, we had retraced the steps of RoadRUNNER’s founders. In the tire tracks of all who had come before us, we created our own version of the story, filled with laughter, mishaps, and quiet moments that will stay with us forever. Route 66 gave us more than just a long trip. It gave us time, space, and perspective. Few things in life make you feel more connected to the world around you than a good, long motorcycle ride.

The California Dream

The ultimate Route 66 destination was often California, the land of golden beaches, endless sunshine, and, of course, opportunity. For many, it represented a fresh start, whether that meant escaping harsh winters, chasing postwar jobs, or simply living out a westward fantasy. Places like Los Angeles and Santa Monica came to symbolize the end of the line and the promise of something better.

Yet, by the 1950s and ’60s, the seeds of Route 66’s demise had already been sown. President Eisenhower’s 1956 Interstate Highway Act launched a bold new era of travel: faster, straighter, and safer roads designed for efficiency. As concrete ribbons stretched across the nation, travel slowly shifted. The road became less about the journey and more about how quickly you could reach the destination.

By the late 1970s, many of the interstates had been completed, and Route 66 towns were bypassed entirely. For the small communities that relied on passing traffic, the impact was devastating. Businesses closed. Town squares emptied. Abandoned motels and shuttered diners still dot the landscape today as ghosts of a more vibrant past. In the rush to reach the California dream, the dreams of countless Americans along Route 66 were left behind. The route was officially decommissioned in 1985.

Here are links to Part 1 and Part 2 of this article series.

Facts & Info

Overview

This section of Route 66 begins in Tucumcari, NM, and ends on the pier in Santa Monica, CA. Along this part of the route, you’ll pass through desert mesas and Native American lands. Through Arizona, the road winds through classic Route 66 towns like Holbrook, Winslow, Seligman, and Oatman, each filled with vintage motels, diners, and unique roadside attractions. Once you reach California, the end is near. You’ll experience the heat of the Mohave Valley before finally finding relief from the heat along the coast in Santa Monica. The official end of the route is located on the Santa Monica Pier.

This route is lined with hotels and motels, many of which are Route 66-themed and cater to road trippers. For the most part, reservations aren’t necessary, unless you want to stay at some of the more popular spots, like the ones mentioned in this story.

Roads & Riding

As Route 66 crosses several Native American reservations, it’s difficult to stay on the original route. I-40 covers a large chunk of it through this region, but you can still find the original alignment on the side road following the interstate in many areas. Oatman Highway is a standout section of Route 66 near the California border and has the most curves and elevation change of any section along the route.

Route 66 is entirely paved, and fuel is easy to find throughout. The long hauls mean a comfortable motorcycle is required, especially if you plan to do this trip in two weeks or fewer. You’ll meet significant traffic only when crossing large cities, like Chicago, Tulsa, or Los Angeles. Although the warmer months are the most likely time one might ride Route 66, if I did it again, I’d avoid doing so during the dead of summer.

Resources

New Mexico True

Visit Arizona

Visit California

The End Was Just the Beginning

Despite its sad ending, the spirit of Route 66 lives on. In fact, without its tragic demise, we wouldn’t have the same kind of experience traveling the route today. Getting decommissioned placed Route 66 inside a living time capsule, preserving the neon signs, mom-and-pop motels, vintage diners, and quirky roadside attractions that define its nostalgic charm. Stripped of heavy traffic and modern development pressures, the road has become a place where history breathes and the golden era of American road travel shines.

I’ll even be so bold as to say that it’s entirely possible the magic of Route 66 would have been lost entirely, had it not been for the introduction of the interstate system. Its glorious if fleeting role as the Main Street of America has been preserved much like the petrified logs of the Painted Desert: through upheaval followed by stillness. What once seemed like the end was, in truth, the beginning of a transformation into something timeless. Route 66 is a living fossil of American culture.

Thanks to the dedication of Route 66 preservation groups and state commissions, the stories of the Mother Road continue to be told. Restored murals, rebuilt gas stations, and revived festivals all celebrate its legacy. For today’s travelers, it’s a journey into the past that no modern highway can replicate. It’s the spirit of Route 66.

Recommended Lodging: El Rey Court

Built in 1936, El Rey Court in Santa Fe, NM, is one of the longest continuously operating motels along historic Route 66. Located on the original pre-1937 alignment—before Santa Fe was rerouted out of the Mother Road—El Rey once served as a key stop for road-tripping motorists seeking authentic Southwestern charm.

Today, the property preserves its adobe-style architecture with cozy rooms featuring tiled floors, wood beam ceilings, and colorful local touches. Strings of dried chile peppers hang from wooden beams on the patio, offering a vibrant nod to New Mexico traditions. Riders will appreciate the outdoor pool for cooling off after a long day in the saddle, and a hot tub perfect for relaxing road-weary muscles. The on-site bar, La Reina, serves excellent cocktails, and local food trucks often park out front.

Find it at 1862 Cerrillos Rd, Santa Fe, NM.

Recommended Lodging: Historic El Rancho Hotel

Located in Gallup, NM, El Rancho Hotel is a beloved Route 66 icon that blends Old West charm with vintage Hollywood glamour. Built in 1936 as a retreat for movie stars filming Westerns in the nearby desert, the hotel welcomed legends like John Wayne, Humphrey Bogart, and Katharine Hepburn. Today, each guest room is named after one of the stars who once stayed there, adding a fun bit of history to every visit.

The hotel has a warm, rustic atmosphere with a grand stone fireplace anchoring the cozy lobby, surrounded by hand-carved wood and old movie memorabilia. It’s a place that feels both historical and welcoming. The on-site restaurant serves up hearty Southwestern fare for breakfast and dinner. I had one of the best chile rellenos I’ve ever tasted, and the steak and enchiladas were equally unforgettable. We wished we could have stayed a second night.

Find it at 1010 E Historic Hwy 66, Gallup, NM.

Recommended Lodging: Wigwam Motel

Built in the 1950s, the Wigwam Motel in Holbrook, AZ, is one of the most distinctive places to stay along Route 66. This retro roadside gem features 15 concrete tipi-shaped (despite the establishment’s name) rooms arranged in a semicircle, evoking the spirit of mid-century Americana. A glowing neon sign, vintage cars parked out front, and a campfire-inspired courtyard make it a favorite photo stop for Route 66 travelers.

Each individual “wigwam” may look playful on the outside, but inside you’ll find all the essentials: a comfortable bed, air conditioning, and a private bathroom. Nearby are several great restaurants as well as a grocery store to stock up. The Wigwam Motel is part of a group of “wigwam villages” that once existed across the country and were built between the 1930s and ‘50s. In addition to this one, two others survive in San Bernardino, CA, and Cave City, KY.

Find it at 811 W Hopi Dr, Holbrook, AZ.

Recommended Lodging: Historic Route 66 Motel

This Route 66 Motel in Seligman, AZ, was built in the early 1980s, before the route was decommissioned. It’s a classic motor lodge with ground-floor rooms you can park in front of. The rooms are decorated with Route 66 memorabilia, and the classic neon sign lights up the night, bringing Route 66 to life in Seligman.

Seligman is a Route 66 hot spot, with many shops, diners, and museums to check out. Everything on the town strip is accessible by walking, so be sure to arrive in Seligman with enough time to explore on foot. We found several interesting collections of vintage motorcycles and other antique stores in the town.